Dark Matters: On the Surveillence of Blackness

Simone Browne. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press. ISBN: 978-0-8223-5938-8** indicates a chapter particularly salient / insightful to my research agenda

Introduction, and Other Dark Matters

Key Concepts

- Epidermalization: "the imposition of race on the body" (pg. 7).

- Intersectional Paradigms: "oppression cannot be reduced to one fundmental type, and that oppressions work together in producing injustice" (Patricia Hill Collins on pg. 9).

- Dark Matters: Like blackholes in cosmology, "the often unvisible substance that in many ways structures the universe of modernity" (Howard Winant on pg. 9). "The surveillence of blackness as often unperceivable within the study of surveillence, all the while blackness being that nonnameable matter that matters the racialized displinary society ... Blackness [is] a key site through which surveillence is praticed, narrated, and enacted" (pg. 9).

-

Surveillence Studies: "How and why populations are tracked, profiled, policed, and governed at

state borders, in cities, at airports, in ublic and private spaces, through biometrics,

telecommunications technology, CCTV, identification documents, and more recenty by way of

Internet-bases social network sites such as Twitter and Facebook. Also of focus are the ways

that those who are often subject to surveillance subvert, adopt, endorse, resist, innovate, limit,

comply with, and monitory that very surveillance" (pg. 13). There is no homogenous state of surveillance,

as surveillance may operate in discrete and nuanced ways, including contextually at specific "sites" (e.g.,

the workplace, the military, or the marketplace). Markers of sites of surveillence may include:

- Rationalization: "Reason, rather than tradition, emotion, or common-sense knowledge' is the justification given for standardization" (pg. 14)

- Technology use

- Sorting: of people into specific categories for management and privileging

- Knowledgeability: Different levels of understanding of surveillence, and willingness to participate, affect how surveillence is used

- Urgency: "where panic prevails in risk and threat assessments, and in the adoption of security measures, especially post-9/11" (pg. 14).

-

Gary T. Marx argues new technologies and practices of surveillance...

- Are no longer impeded by physical distance.

- Allow data to be easily shared, stores, compressed, and aggregated.

- Is often undetectable, either by being disguised (e.g., undercover agents) or by being digital.

- Is often done without consent, or knowledge, of the target.

- Is about preventing or mitigating risk through prediction.

- Is now less labor intensive, making it easier to expand monitoring.

- Is not only wearable, through devices like fitness trackers, but relies on people tracking themselves.

- Guilt is presumed based on someone's categorical assignment.

- Is bodily invasive.

- It's intense and difficult to avoid, making uncertainty over being surveilled a strategic characteristic of surveillance.

- Panoptic Sort: "The processes by which collection of data ... is used to identify, classify, assess, sort, or otherwise" control and define life (pg. 16).

- Surveillance Assemblage: "Sees the observed human body 'broken down by being abstracted from its territorial setting' and then reassembled elsewhere (a crediting reporting database, for example) to serve as virtual 'data doubles' and also as sites of comparison" (pg. 16).

- Racializing Surveillance: "A technology of social control where surveillance practices, policies, and performances concern the production of norms pertaining to race ... [signaling] those moments when surveillance reify boundaries, borders, and bodies along racial lines, and where the outcome is often discriminatory treatment of those who are negatively racialized by such surveillance ... [It] is not static or only applied to particular human groupings, but it does rely on certain techniques in order to reify boundaries along racial lines, and, in so doing, it refies race" (pg. 16-17).

-

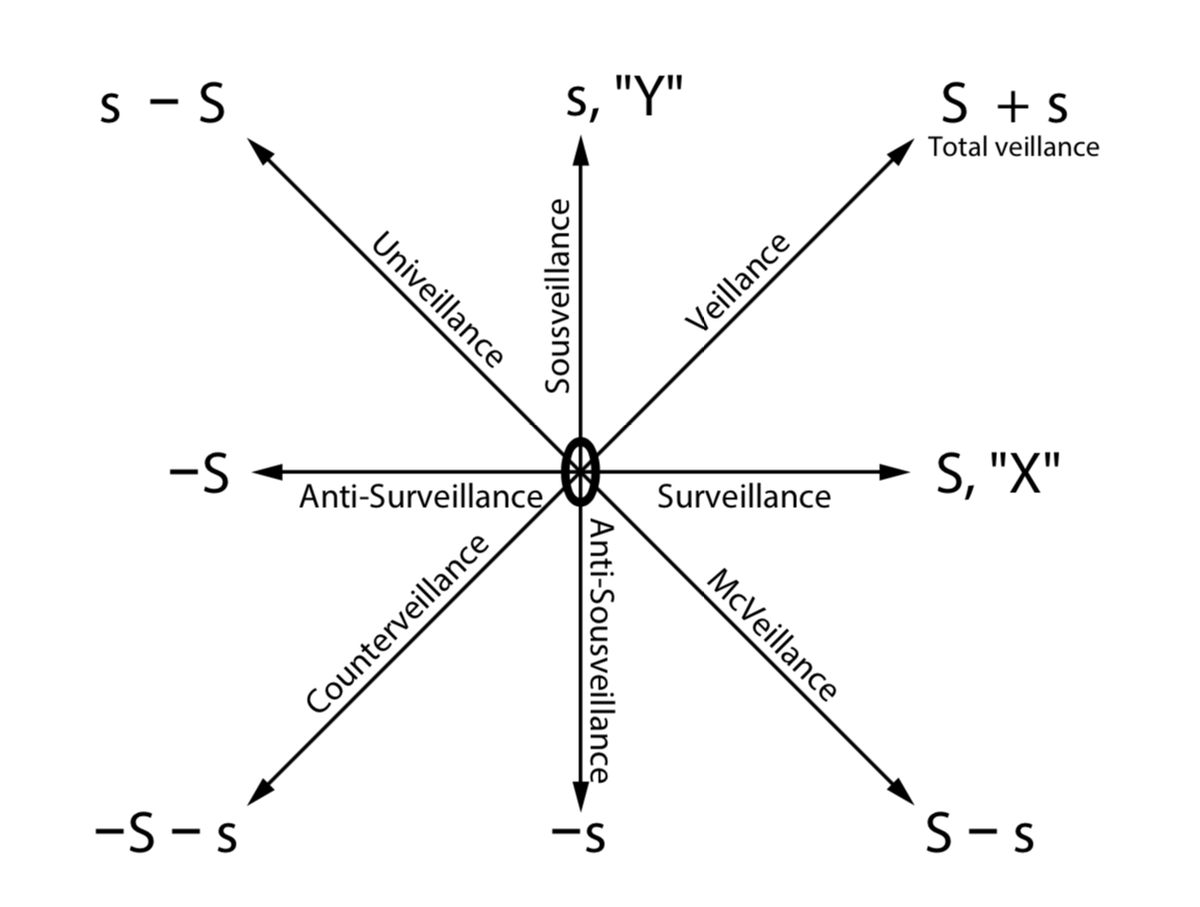

Sousveillence: Veillence, being a neutral form of watching. If surveillance is the watching of people by

entities in positions of power, than sousveillance is its oppositional inversation of power relations. "'Observing and recording by an entity

not in a position of power or authority over the subject of the veillence'" (e.g., recording police

brutality) (pg. 19).

- Dark Sousveillance: "The tactics employed to render one's self out of sight ... an imaginative place from which to movilize a critique of racializing surveillance, a critique that takes form in antisurveillance, countersurveillance, and other freedom practices" (pg 21). "How certain surveillance technologies installed during slavery to monitor and track blackness as a property ... anticipate the contemporary surveillance of racialized subjects, and ... how the contemporary surveillance of the racial body might be contended with" (pg. 24).

Chapter 1 | Notes on Surveillance Studies: Through the Door of No Return

This chapter rethinks the surveillance prison, The Panopticon (1786), theorized by 18th century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham through the layout of the slave ship, Brooks (1789).The Panopticon

Originally imagined as a model for workplace supervision, the Panopticon was imagined as an all-seeing architectural design with many functions - prisons, but also schools, factories, etc. Intended to be "control by design" (pg. 34), Benthall designed a systems of circular cells surrounding a central watchtower. Prisoners would be watched from inside, from the tower, or from outside, through the windows at the back of each cell, but they would not see or communicate with one another. At night, mirrors would reflect lamplight so that prisoners would be unable to see if there was a guard in the tower. The intention was to enact a covert power over prisoners, where they, unable to tell whether they were actually being watched at any given time, would self-discipline.Other conceptions of surveillance inspired by the Panopticon:

- Synopticon (Mathiesen, 1997): "A reversal ... where the many watch the few in a mass mediated-fashion" (pg. 38).

- Banopticon (Bigo): Where certain groups are labelled as dangerous to the state, and security measures are predicated on that risk (pg. 38-39).

Some surveillance scholars no longer view panopticonism as useful in the digital age, arguing that "'post-Panoptical subjects reliably watch over themselves' without need of the physical structure of the Panopticon" (pg. 39). Some argue that the culture of social media makes people seek out being watched, thus disciplining themselves by giving endless amounts of data to others, companies, and governments.

The Slave Ship and Plantation as Sites of Surveillance

Browne points out that the slave ship, a floating prison, predates the contemporary prison on land we are familiar with. The diagram of the slave ship Brooks was designed so that it met the legal requirements of the Dolben Act of 1788, which regulated the overcrowding of slave "cargo" on ships (pg. 46). Able to carry over 600 captured people below board, the slave ship was designed with "strict discipline" in mind (pg. 47). Like the protagonist of Phillip's "Cargo Rap," the slave ship is a prison also in its enacting of a slow-motion death (pg. 48). The positioning of slaves by gender in the cargo holds was also fueled by intent to streamline surveillance. Plantation surveillance, including the use of "slave passes" governing when and where slaves could go, can be considered "the earliest form of surveillance practices in America" (pg. 52). Brown describes a specific "runaway slave" advertisement for a young girl of mixed race who would perform whiteness within plain sight, donning makeup and using an alias as an example of dark sousveillance.The Census

The first federal U.S. census was in 1790, employing "racial nomenclature" to define who in a household was a free and white, male or female, or enslaved (pg. 55). The 1850 U.S census was the first to include "slave schedules for some states in order to enumerate each enslaved person held in a household" (pg. 55). The census freezes a census taker's identity in one specific time and reinforces racial (and other) categories. Given that racial categories on the census have evolved and changed many times, how that data is then recollapsed for analysis also always reifies these categories.Chapter 2 | "Everybody's Got a Little Light Under the Sun": The Making of the Book of Negroes

"The Book of Negroes is an eighteenth century handwritten ledger that lists three thousand self-emancipating ex-slaves who embarked mainly on British ships during the British evacuation of New York in 1783" (pg. 66-67). It is considered one of the first government-issues documents regulating U.S. migration that also linked bodily markers to the right to travel. This chapter focuses on text-based technologies for surevilling Black bodies. Surveillence of black bodies "was integral to the formation of the Canada-U.S. border" (pg. 69). Detailed bodily descriptions were written down in both "The Book of Negroes" and in "fugitive slave" advertisements. These descriptions allowed the white public to constantly keep eyes on black bodies, searching for those who should not be out and about.Black Luminosity: "A form of boundary maintenance occurring at the site of the black body, whether by candlelight, flaming torch, or the camera flashbulb ... an exercise of panoptic power that belongs to, using the words of Michel Foucault, 'the realm of the sun, of never ending light; it is the non-material illumination that falls equally on all those on whom it is exercised'" (pg. 67). However, Brown asserts this light is shined more brightly on specific people.

Boundary Maintenance: In this case, "tied to knowing the black body, subjecting some to a high visibility ... by the way of technologies seeing that sought to render the subject outside of the category of human, un-visible" (pg. 68).

Performative Sensisibility: Internalization of potentially being watched impacts our behaviors, even when we are not being actively watched.

Visual Surplus: How the visuality of Black pop culture is made available/spread through the use of new technologies (e.g., recording street performances on your phone).

Chapter 3 | Branding Blackness: Biometric Technology and the Surveillance of Blackness**

This chapter focuses more on Fanon's concept of epidermalization, "making bodies meaingful by endowing in them qualities of 'colour'" (Gilroy on pg. 91). Brown discusses the branding of slaves as our "biometric past" in order to "think critically about our biometric present" (pg. 91). Branding acted as a biometric technology, "as it was a measure of slavery's making, marking, and marketing of the black subject as commodity" (pg. 91). Branding acted both as corporeal punishment and a method of identification. The brand "denoted the relation between the body and its said owner" (pg. 93). Branding was a technology of racial categirization, "a dehumanizing process of classifuing people into groupings, producing new racial identities that were tied to a system of exploitation" (pg. 94). Further, the One Drop Rule was used to brand blackness in order to maintain the enslaved body as black (pg. 92).Similar to Bowker and Star's torque, Browne discusses epidermalization as "the moment of fracture of a body from its humanness, refracted into a new subject positions" (pg. 98). Epidermalization is the creation of Blackness through a white gaze, producing negative stereotypes and objectifying the Black body. The body, both with brand and without brand, is seen as a text which can not only be read, but written on.

As with other eugenicist views and policies, those deemed disabled were viewed as undesirable: "the surgeon's classificatory, quantifying, and authorizing gaze sought to sinlge out and render disposable those deemed unsuitable" (pg. 95). Browne discusses this "naturalization of difference" as "aimed to fix social hierarchies that served ... colonial expansial, slavery, racial typology, and racial hierarchiization" (pg. 96). Anti-Black discourse took the familiar framing of "scientific," such as Edward Long's taxonomic portrayal of Black Jamaican men as "innately primitive and corrupting" and Black Jaimaican women as servile and sexualized (pg. 96).

Differing from scientific racism is "commodity racism," more accessible to those beyond the scientific and literate elite, portrayed through stereotypic marketing. In more modern terms, Browne describes the example of people selling branding instruments on eBay, "that being to consume while at the same time alienating Blackness" (pg. 105). Keith Obadike, who countered commodity racism by listing his own Blackness on eBay, described the Internet's many interfaces as harkening to racist colonial narrative: "There are browsers called Explorer and Nagivator that take you to explore the Amazon or trade in the ebay" (pg. 106).

Digital Epidermalization

Digital epidermalization is "when certain bodies are rendered as digitized code, or at least when attempts are made to render some bodies as digitzed code ... where algorithms are the computational means through which the body, or more specifically parts, pieces, and, increasingly, performances of the body are mathematically coded as data, making for unique templates to computers to then sort by relying on a searchable database, ... or to verify the identity of the berarer of the document within which the unique biometric is encoded" (pg. 109). "Digital epidermalization is the exercise of power cast by the disembodied gaze of certain surveillance technologies ... that can be employed to do the work of alienating the subject by producing a truth about the racial body and one's identity (or identities) despite the subject's claims" (pg. 110).The Keeper of Keys Machine developed by Marc Bohlen for the Open Biometrics Initative, which argues against the false notion that biometric machine learning is infallible and confirming. Instead, it drives home that such "decisions" are probabalistic, an approximation (pg. 116). The fingerprint scanner shows the user an "open list of probable results" to make the system more transparent (pg. 117). The idea behind this is to promote a critical biometric consciousness, pushing people to question the use of biometric data and the history of biometric technologies.